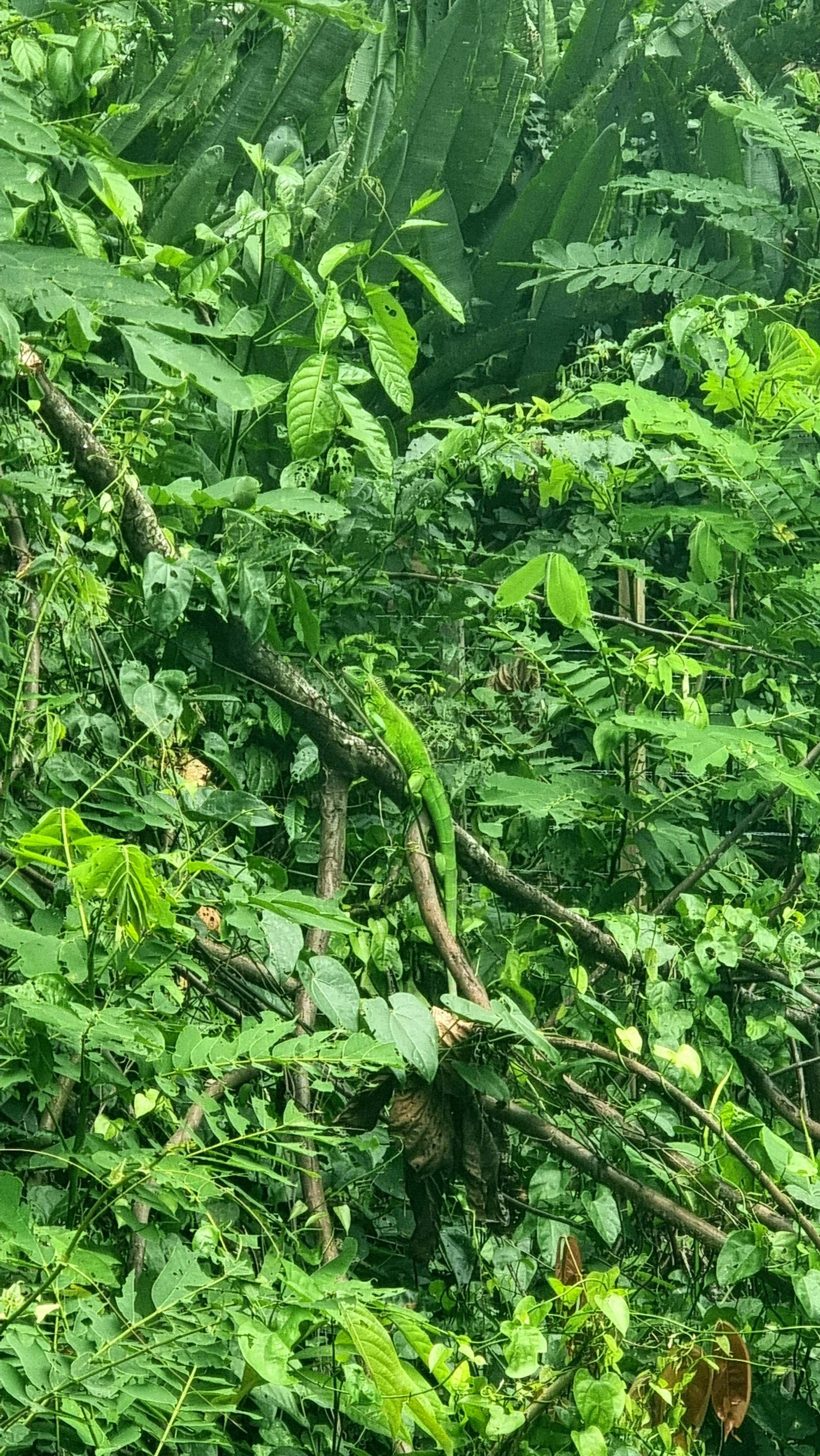

Welcome to the Jungle

This entry will attempt to cover some of the second week of our spontaneous South American adventure. It is the week of the ayahuasca retreat - my return to the jungle, and to the place of healing and rebirth that supported me so well in the aftermath of my first confrontation with cancer back in 2019. It is a strange journey, and though I can only really report on my own experience of it, I will do my best to cover it all. Let’s dive in.

We awoke the morning after our arrival in Iquitos in a little room at the La Casona Inn, where we were due to meet up with the rest of our group, and took our things up to wait in the courtyard. There were several people seated at the tables, but none from our retreat. Our uncertainty grew when the meeting time crept closer, with no new people having arrived, until, eventually, an old woman called out to ask if any of us were waiting for Arkana. When we and another couple replied that we were, she told us that the Arkana group were all waiting at La Casona Hotel — not La Casona Inn — and to book it to the correct location. We quickly bustled out of the building and flagged down the nearest tuk-tuk driver, piling our bags into the back as we hopped in. It was only a five minute drive, and we arrived only somewhat flustered from the last minute rush. After a brief meet-and-greet, a waiting bus drove us two hours through the wilderness to a small port town, scattered across the bank of one of the many branches of the great Amazonian river system. It was another hour from there by boat, and our group munched on fruit and sipped on cold juice as we flew across the surface of the wide, brown river, winding deeper and deeper into the jungle proper.

On our way

Down a few of the tight passages that thread their way through the thick reeds, and we had arrived. Arkana Spiritual Centre consists of a primary cluster of huge, open, circular buildings made of wood and thatch, connected by a web of walkways that lead off in different directions. A broad section of decking by the entry accommodates a pool in its center. Walk the narrow, rickety boardwalks to the right and you will end up at the rooms. Walk off to the left and you encounter the large, blocky building that houses the communal meals; take the stairs up and you will find a chillout space, ringed with hammocks that look out over the river and the twisting shapes of the jungle beyond. The layout of the buildings is such that each is connected to all the others; an interconnected pattern, with each building as a node on the network. Upon our arrival, the staff struck up a welcoming song with drum and maraca, and we were each given a cold glass of water and a cool, damp towel as we were ushered in.

A cheerful American man greeted us at the entrance awning and introduced himself as Cesar. Cesar was to take the time to show us around Arkana, shepherding us from building to building and filling us in on the finer points of our retreat lifestyle. He pointed out the blackboard in the kitchen, which would show the schedule for each day; and the blank blackboard upstairs, which was ours to decorate as we wished over the course of the retreat. He showed us the exercise room and the therapy room above; and the main maloca, which would serve as the ceremonial space. He even had a prop toilet set up, to show us how to go about our business in the jungle (do said business, heap woodchips on the result, rinse the bowl with a squirt bottle). When the tour was over, we had time to settle into our rooms. The outer walls were little more than stretched mosquito netting, giving us an unobstructed view into the dense jungle just beyond the perimeter. Lunch followed - one of many delicious buffet-style meals, using only fresh ingredients and with minimal salt or oil. We ate crumbed and roasted catfish and other delicate dishes, as we got to know some of the others in our group.

The majority were American, with an older couple from the Netherlands. The older couple, Rene and Suzanne, operate a centre for spiritual and shamanic work in Amsterdam. There was Adam, a yoga instructor; and his partner, Stephanie, who was studying various healing modalities in her quest to support others. Keith was an artist out of Colorado, whose special talent for metal sculptures had evolved from a casual hobby into a fully-fledged commercial undertaking. The others — Nicholas, Michael, Kim, Neida, Laura, Angelica, and Naz — we would get to know over the course of the next few days, developing the deep connection that naturally forms through the shared intimacy of the retreat.

Delicious

When we had all eaten our fill, we wandered over to the main maloca. It was an open, circular space, with individual mats circling the outer perimeter. Looking up, you could not help but be mesmerised by the intricate webbing of support beams, radiating out from a central axis and layered in smaller rings to reach a sharp point at the top. As we sat in our circle, we were given the opportunity to properly introduce ourselves, and to meet our hosts.

There were three main facilitators, apart from Cesar: Imani, Chandler, and Vint; and the three shamans who would guide and support our internal journey over the course of the week. The shamans were all of the same family, and came from the Shipibo tribe, which dwelt deeper in the jungle, four or five days away by boat. As we finished with introductions, the shamans discussed ayahuasca, which they referred to as “the medicine,” focusing on the proper relationship to cultivate with it in order to facilitate the inward process of healing and growth. The most important point was this: surrender. Surrender to the medicine, and Mother Ayahuasca will give you what you need - though not necessarily what you want. Remain open and accept what comes, and the medicine will do what it needs to do. The ayahuasca drink is brewed by combining the ayahuasca vine with chacruna leaves, boiled and reduced over several days to a treacle-like consistency - though, as many who were not aware would soon discover - the taste itself is far from treacle-like.

We broke off for a time, and were called back into the maloca one-by-one as the sun set, to discuss our context and intentions in working with ayahuasca. The candlelit room was vast and intimidating this time, with a single mattress in the center, the facilitators and shamans seated by the far wall. When it was my turn, I stepped into the center of the room and sat down, speaking of my history and the journey to my present condition. I expressed my desire to integrate with what Jung refers to as ‘the Shadow,’ so that, if death is indeed coming for me, I might face it with as much of myself as possible.

The jungle was beautiful that night. The buzzing and droning of insects mingled with the cries of birds in the heavy, wet air. The silhouettes of monkeys could be seen in the middle-distance, swinging from tree to tree. The introspective energy of the evening carried on through dinnertime, and swept us quickly and quietly into sleep.

The dining hall and pool

…

The next day was spent in preparation for the first of the ayahuasca ceremonies, which would be held that evening. The morning began with a formal ceremony in the sapo maloca. We chanted mantras and shook maracas as a candle, representing both the soul and the cleansing flame, was held aloft. Our foreheads were daubed with a red paste and a flower was placed in each of our laps, to welcome us into the space.

A second ceremony followed the first: the ceremony of liquid rapé. Rapé is a blend of jungle tobacco and other sacred plants, and is administered through the nose, cleansing and grounding the mind of the user. This process was held in the main maloca, facilitated by the shamans and their helpers. Two beds were set up in the center of the room, where we were laid down, two at a time, to receive the medicine. Once we were comfortable and had taken a few deep breaths, the shaman poured a small spoon of the liquid into each nostril, which trickled through the nasal canal and set the eyes streaming. We waited a moment, then sat up, allowing the mixture to drip from our mouths into a ready bucket. It was like snorting a mild wasabi, and we were all blowing our noses and spitting into our buckets for some time afterwards. Still, it really did clear the chest and sharpen the senses.

By the time we had finished, breakfast was ready. We indulged gratefully, for it was already late in the morning, and we were to fast beyond 3:00pm. We had an open schedule until after lunch, and I took the time to update my journal and read a little in the upstairs hammocks, while Alessandra took a dip in the pool. We stuffed ourselves with lunch when the time came, and the bell soon called us to the next activity. As a group, we jumped into one of the boats moored on the river bank by the entrance and travelled downriver. Several pink dolphins joined us for part of the way, and we eventually pulled up near a copse of tall trees with tangled branches. Then, we saw movement, and several wooly monkeys clambered down from the trees to say hello. Our guide tossed fruit to them (much of which they spectacularly failed to catch), and one even scampered onto the boat with her baby, settling on the prow to eat her prize.

Wooly monkey want banana

Clouds gathered as we made our way back, replacing the blazing heat with a startling coolness. When we arrived, it was time for our next activity, and we each carried a bucket of murky green water carefully from the maloca to the entrance, having been instructed not to spill a drop. These were for the plant bath - a mixture of sacred and medicinal plants, created and blessed by the shamans; and used to protect us during the night’s ceremony. We saturated the mixture with our hopes and intentions for the evening’s work, before tipping it over our heads and bodies. For the protective qualities of the plant bath to remain, we were instructed not to wash or towel off, and so did our best to air dry, prior to changing into light, loose clothing. The rain came just after, and we watched it drench the world from the front awning before parting ways. It was the hour before the first ceremony - a time for quiet contemplation; the calm before the storm.

When we returned to the main maloca, it was 8:15pm, and the ultramarine blue of the evening was punctuated by the brilliant light of the candles burning in the center of the space. I sat on my mat in the outer ring, observing that an inner ring of mats had been set up for the shamans, encircling the burning candles. To my right was a bucket, a roll of toilet paper, and a flashlight. Ayahuasca is a purgative, and it is believed that the purging that occurs during ceremony - which can present as vomiting, going to the toilet, yawning, shaking or even crying - is the body cleansing and ridding itself of negative energies. The flashlights produced a dim red light when turned on, and would serve to guide us out of the maloca and to the toilets down the hall, without disturbing others’ in the process. The shamans entered in ceremonial dress, lowering themselves to their mats and setting up. Two glass jugs of purplish liquid were laid down beside a clinking tray of glasses, and I shuddered involuntarily, a primal memory of the flavour returning to me. For the first ceremony, we were told, doses would be standardised. There would be an offer for a second dose after the first hour, followed by a third (only on the first night) an hour after that. After the first ceremony, our doses would be adjusted based on our experience.

I looked over at Alessandra, who was watching the process unfold with undivided attention. I was excited — and nervous — for her. It would be her first time having ayahuasca, and she’d had precious few experiences to prepare her for the kind of inward journey it would be. Over the past several years, I have discussed my first retreat with her on multiple occasions, but description alone inevitably falls short of experience, and I knew it was difficult for her to truly understand what I’d seen and felt throughout that time. The only way was for her to see for herself. The thing is, you don’t get to choose where you go — and there was no way of knowing what kind of ordeal Alessandra might face. I knew from past conversations that she had many closed doors in her — some locked up tight and buried so deep that she could no longer say what was behind them. Without doubt, ayahuasca was capable of helping her to open these internal spaces. What we could not predict was what would happen as a result.

The intricate ceiling of the maloca

Two by two, we were called up to drink. When my name was called, I rose from my mat and sat cross-legged across from the shaman. He held the small glass to his heart-space, silently blessing the ayahuasca before handing it to me. I, in turn, repeated my intention as I held the glass close. Please help me to integrate my Shadow. Then, before I could think, I downed the contents. Ayahuasca, to me, tastes like what you might get if you made an alcohol by fermenting black olives. The flavour, thick and horrid, is bitter and sour in turns. It burned as it glugged down my throat, stopping to settle somewhere in the center of my chest, clinging to my insides and coating my tongue with a thick film. By the time we had all drunk, the candles were blown out, throwing the room into darkness.

I felt nauseous almost as soon as I returned to my mat. It hung in my solar plexus, bubbling and burning, begging to be purged, but I waited, focusing on my breath. Each ayahuasca experience is different, and each person responds differently, but I recalled from my last visit that if I could overcome the initial wave of nausea, I would be able to handle the rest. Alas, the nausea built to a crescendo and, at its insistence, I walked to the bathroom and threw up violently in a provided bucket.

I thought the purge would kick off the inner journey, but it didn’t. After the first hour or so, the medicine begins to work, with flickers of a kind of synesthetic attunement with the world slowly opening up the internal space. It is when the shamans start to feel these flickers that they begin to sing, calling to the spirits of the medicine and weaving a protective web around the maloca with their music. You can feel it, too - the moment the singing begins, it is as though the medicine rises and uncurls inside of you; like a cobra, swaying to the melody of a snake-charmer’s flute. The shamans had begun their song, but apart from an internal loosening and opening, I noticed little effect. I took a second dose when it was offered - and then a third when, an hour later, I remained firmly grounded in material reality. The nausea held me far longer than I’d anticipated. Then, slowly, things began to shift.

Ayahuasca ceremonies often follow a specific pattern. In a set of four, the first ceremony is frequently a purging and cleansing - a dredging up of the emotional and physical muck. The second often begins the deep work. The third is typically a beautiful journey into love and light; and the fourth ties up the work done and seals the process. This has certainly been my experience. After the initial wave of icaros (shamanic songs), one of the facilitators began to sing. She had a beautiful voice, and the song was sad, full of heartache and longing. A tremendous grief welled up in me, rolling over me in waves, ripping away my breath in great sobs that wracked my body as my eyes filled with tears. Without warning, a dam in my heart that I hadn’t even known was there disappeared, letting a deep sadness crash through my soul in a flood. I realised that, despite my courage in facing death, I am still afraid. Not of death itself, however. I am afraid because I do not want to die. This was a painful and overwhelming realisation, but it was an ecstatic, cleansing pain, almost sweet in its raw purity, and I was grateful for it.

I had not allowed myself to feel my own grief - even to realise its existence - and had walled up the emotion in my heart. This repressed emotion is the very substance from which the Shadow is formed; and so, in releasing my grief, I released my Shadow. He came to me, hugging me in my anguish. His touch was soothing, and when I was empty and still, he clasped my arm.

“You are my brother,” he said. “Whatever comes, we will face it together, and we will always have each other.” His words brought with them a fresh surge of emotion, for though I am blessed with the support of friends and family, the lonely path to death is ultimately walked alone. For the first time, in that moment of grief, I realised that I have myself. I am not alone, after all.

”You’re allowed to feel happiness too, you know,” he added gently, with a wry smile.

It was as though the work had been done for the evening, and the experience gave way to an internal stillness, ebbing and flowing with the music and the icaros as I pondered my newfound grief. I had found and connected with my Shadow by finding and connecting with my sorrow, and I felt whole; at peace. In the final third of the evening, we were called up one by one to receive our personal icaros. I sat on the mat in front of one of the shaman, an impenetrable dark mass swaying from side to side, and he sang to me, working directly with the material of my internal landscape. It is difficult to describe the quiet reverence that settles over the mind when seated before these singular people, as they weave their music around and through you. When it is done, mazpacho is blown over the hands and head, and a facilitator guides you back to your mat.

The shamans and facilitators continued to sing into the night, playing guitars, harps and flutes to pierce the darkness as the group lay back on their mats, thoughts turned inward. In my own internal stillness, I realised one more thing: I may be as a tree, standing alone and reaching for the light; but I am also a forest, deep roots intertwined with my fellows in the shared struggle of life. And if one tree falls, the forest remains. This notion was comforting - a reminder of the broader continuity of spirit beyond individual death. Finally, in the early hours of the morning, the facilitators announced an end to the ceremony. Candles were lit once more, and fruit was brought out.

The ceremonial maloca — picture taken during my 2019 retreat, though little has changed

I stared into the candle flames for a long time, then moved to Alessanra’s mat to check in on her. She had met Mother Ayahuasca and been shown the doors within, but so far was thwarted in her attempts to open them. Whilst she had her own insights throughout the ceremony, she had felt deeply nauseous, only managing to purge when it was finally over. Cesar gave her a glass of lime juice to quell the nausea, but the taste was overpowering and the relief only temporary. When we returned to our rooms, she sat on the floor with a bucket for a long time before the discomfort passed enough to sleep.

…

It was the morning after our first ceremony, and we awoke refreshed, despite only having had a handful of hours to sleep. We mustered in the yoga shala and moved through a yoga flow, limbering up sluggish muscles and unifying mind, breath and body. My inflexibility makes yoga one of the most challenging forms of exercise for me, but perseverance got us through to the breakfast bell. Alessandra continued to feel unwell throughout the morning, picking half-heartedly at her breakfast and questioning if she would even drink for the second ceremony.

Alessandra was out by the pool when one of the staff approached her. Back in 2019, I got to know Jose, the owner of Arkana, who was attending the retreat with us. As we locked in the current retreat, I sent Jose a message, letting him know that I’d be returning with my fiancée, explaining our situation and asking if he would be there this time as well. He replied that he would not — but he was glad I was returning, given the context. I thought no more of it, but when the staff member came up to Alessandra, she advised us to pack our things — Jose had upgraded us to the private suite for the remainder of the retreat. The suite was located in a far section of the complex, and boasted its own shower and toilet, a double bed, a powerful fan, and plenty of space. This kind gesture exemplified the spirit at the heart of Arkana, and Jose’s thoughtful generosity touched us deeply.

After eating, it was time for the first groupshare, in which each person was given the time and space to relay their experience of the first ceremony, and any insights gained in the process. My heart was still raw from my own discovery, and the grief I had found within welled up to the surface in the telling - yet it was cathartic, in its way.

The suite

When groupshare was over and the others got up to leave, I remained behind to speak with the shamans. I wanted an opportunity to ask them what they felt I could do to help myself in my current situation. As it stands, my prognosis is poor, and the only treatment that seems even somewhat helpful is that offered by the upcoming clinical trial in Perth. If the cancer spreads, I would first need to confirm my eligibility for the trial; and even then, there is no guarantee I would be in the treatment group receiving the more effective experimental treatment. To top it off, even if I am lucky enough to make it into the study and the experimental treatment group, the medication only shrinks tumours in 55% of patients. There is so much being left to chance, and I refuse to shrink away from anything that could increase the odds in my favour. The shamans listened patiently as I outlined the nature of my situation in more detail, and then gave me their views.

The shamans each took a turn in speaking, but their responses mirrored one another. They were willing and able to help me, they said — and they would continue to work with me in ceremony through their icaros — but four ayahuasca ceremonies would not be enough to heal my body. There are many plants that can serve me, they continued, but the process would take time. Four weeks, they estimated, would be enough. Four weeks at the retreat on a specific plant dieta, with the treatment overseen directly by the shamans themselves.

One of the shamans told me that he empathised with my situation, as he himself had previously been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and given a month to live. “But I’m still here,” he finished.

They would not pressure me to stay and proceed with the treatment, they concluded, but they could help me. I was told to think it through carefully, come to my own decision, and let them know what I wanted to do.

My mind was reeling at the unexpected offer as I exited the maloca. I had previously only considered the clinical trial in Perth as an available treatment option, and the risks and time required to trust in the shamans and their approach would be high. Yet it was only a month, and it would not preclude me from pursuing Western treatments back in Perth…

It was not something to think about right away, at any rate — with our new apartment being renovated and the next lot of scans coming up, it would be necessary to return to Perth as planned. However, if the scans proved to be ominous, a return to the jungle was not to be ruled out.

The riverbank outside the retreat

But this is all tangential for the time being — back to the story. From the maloca, I walked up to the therapy room, where I had booked in for a round of ‘lucia light therapy.’ The therapy, developed in a partnership between a psychotherapist and neurologist from Austria, involves a lamp that strobes and flickers white light over the participant, who lies underneath it with closed eyes. The effect is remarkably similar to a psychedelic experience - I perceived a kaleidoscopic shifting of colour, geometry and movement flowing through my mind, as though I were seeing the space within, rather than the light without. The process is designed to support accessing a deep meditative state, and, though I am somewhat skeptical of these modalities, I cannot argue with the results.

As the afternoon baked the ground in the relentless heat of the sun, our group walked along the riverbank to the nearby village of Libertad. The village has been growing and expanding since my last visit, yet the police station remains a rickety hut with no door; a single chair in the corner serving as an overnight gaol cell for the odd villager who was out causing problems. The houses were all built on stilts to account for the wet season, which can see the water line rise up several meters or more. As mercurial weather shifted in moments from agonising heat to a cold rain shower, we walked over to the village school, where a market of handmade trinkets and crafts was laid out for our benefit. We each bought necklaces and bracelets with small pieces of ayahuasca set into the weave, and gave over the bagful of coloured pencils and paper that we had brought for the children.

The police station, with room for one rulebreaker

When we returned to Arkana, it was time for the pre-ayahuasca ritual of the plant bath, followed up with a breathwork session to leave us calm and centered ahead of the next ceremony. One hour of quiet contemplation and the time had come once more. We made our way to the maloca, and I could not wait to see what discoveries would be made this time around.

Precious little, I was disappointed to discover. Ayahuasca gives you what you need, not what you want — and what I needed was a lesson in humility. I had previously taken 60mL of the brew in three servings, and it was recommended that, for this ceremony, I take the full 60mL as an initial dose. I had never taken quite so high a dose before, and was bubbling with anticipation over what I would experience. So much so, in fact, that I spent much of my time trying to make something remarkable happen. It felt like those dreams about flying that come from time to time, in which you manage to take off, only to skid back to the ground. Every time you take to the air, the ground pulls you back — and the more desperately you seek to soar, the more firmly you are grounded. I felt flickers of the medicine activate in my mind, yet I pulled at it greedily, seeking to direct it — to force visuals where none were forthcoming; to imagine interactions that were shallow and fabricated.

After staying with the nausea for some time, I finally gave up the struggle and purged into my bucket. I had hoped that, with a larger initial dose, I might circumvent the need for a second; but when the second dose was offered, I was one of the first up, padding over to the facilitator’s mat in a state of stone-cold sobriety. I held onto the second dose for longer still, straining to begin the inward journey, and when I finally purged for a second time, I could feel the effect building once more…only to dissipate entirely when I returned to the mat. This time, it was gone for good. I lay, shifting uncomfortably on my mat, listening to the icaros and trying with every fibre of my being to reconnect with the medicine, but to no avail. I had tried to lead the experience, seeking to replicate the joys of previous journeys, and the true experience I might have had fizzled out as a result of my grasping.

Many beautiful songs were played over the course of the evening, and my exhausted mind slipped in and out of a dream-like state, the music winding a path for my imagination to follow. I came out of the trance again and again, abruptly snapping into a perfect lucidity. I wondered how much longer it would last, for I was uncomfortable and deeply tired. The night was endless, and at one point I wondered if I had somehow missed my personal icaro, so sure was I that the session was drawing to an end. But no, the personal icaros were still to come. The night drew on, and I was relieved when the voice came to say the ceremony was over. I soon went to check in with Alessandra, finding her nauseous once again — albeit less so than the previous night. Keith, Naz and I stayed up for some time as Alessandra drifted into sleep, speaking of philosophy and religion until we could not stay awake any longer.

Despite my disappointment, I did feel cleansed and spacious inside; and I had learned my lesson — I would not try to lead my next journey, no matter what.

…

Our week at the retreat was so densely packed with experiences and insights that even this extended post can only cover a fraction of the whole — with the most profound experiences still yet to be described. Though the lessons learned over the course of the week are all interconnected, we must do our best to stick to our structure. So, here are some of the things I have taken from our first three days in the jungle:

There is power in ritual, for ritual acts out the symbolic content of the unconscious. When we create a connection between the content of the unconscious and the physical world, strange and transformative things can happen. In other words, when we engage and make use of more than our conscious minds, we can change more than our conscious minds.

On the internal world:

It is possible to repress emotions to the point that we do not realise they are there. Nevertheless, a repressed emotion always finds its way to the surface. When something you do, say or feel is unexpected or surprising — particularly if it is mismatched to the context it arose in — you might question if there is an emotion you are not allowing yourself to feel.

Emotions demand to be acknowledged; and, in allowing them in, we also allow in the parts of us that can help to guide us through the challenging experience. An emotion that is not heard when it whispers will soon begin to scream. If it isn’t heard then, it may well begin to wreak havoc in its desperation to be attended to.

We may consider the conscious, rational ego mind sovereign; the unconscious, emotional mind as subservient and weak (which is absurd, given how rarely we can order ourselves about successfully); yet if we treat the unconscious as unnecessary and superfluous, we are cutting ourselves off from the majority of who and what we are, and all the crucial information that only it can provide.

Following from the above: in life, we do not lead. We listen, aim, and follow. If we try to lead, we are denied the deep and humbling experience of being part of something greater. Do not pick a goal and drag yourself to it. Listen to your values, your intuition, and what resonates. Set your aim based on this, begin to walk in a manner that the internal voice does not protest to, and allow yourself to be lead. I should not that I do not mean the path should avoid difficulty — naturally, the most important path will be the most difficult — however, there are different kinds of internal resistance, and it is important to know the difference between moving toward a valued, resonant goal; and forcing yourself toward something desired only by the ego, using methods that go against your natural rhythm. Set your intention, listen, aim, and follow. Do not impatiently force experience.

Kindness is everywhere — all that is needed to tap into it is to practice it oneself.

Death is not an end, but a return to the Whole. In this way, it can be seen as beautiful and glorious, rather than merely tragic.